News

James Penfield Seiberling - July 3, 1898 - October 13, 1982

Biographical Essay on the Life of JAMES PENFIELD SEIBERLING July 3, 1898-October 13, 1982

By Harriet D. Chapman July 3, 2020

If your birthday is July 3, you share it with James Penfield Seiberling, a native of Akron, who was born the day before Independence Day in 1898 and died October 13, 1982. Frank “F.A.” and Gertrude Seiberling and their family had a very busy summer in 1898. Not only was it a summer during which F.A., his brother, his brothers-in-law and close business associates were planning how to make a tire and rubber products plant out of an old strawboard factory that he had just purchased, it was also the summer in which his and Gertrude’s long-awaited fourth child would be born. On July 3, 122 years ago, James Penfield Seiberling entered the world at the family home at then-528 (later 158) East Market Street, near its intersection with Prospect Street. With two brothers and a sister six or more years older, this little boy would be closest in age and kinship to his younger sister Virginia, who was born just 14 months later. Blue-eyed and blonde-haired, he resembled his mother and was aptly named for his maternal grandfather, brick manufacturer and inventor James Penfield, of Willoughby, Ohio. He would be called by friends and family by his nicknames, “Penny” or “Pen,” from an early age until his death.

Penfield Seiberling was born amid national and local news of great concern and interest: the Battle of San Juan Hill in Santiago de Cuba had taken place just two days prior, on July 1, 1898. It was the largest land victory of the Spanish-American War. Future President Theodore Roosevelt had led his Rough Riders in what also became the bloodiest battle of that short war, which had begun in April. A fellow Akronite, Theodore W. “Thede” Miller – son of well-known industrialist and Chautauqua Institution founder Lewis Miller, and younger brother-in-law of Thomas Edison – was a Rough Rider who was shot during the battle and died as a result of his wounds five days after Penfield was born.

Young Penfield grew up attending the Bowen and Henry Schools in Akron. The streets, parks and hills of Akron were the playground for him and his neighborhood mates. He played baseball, and he gained a lifelong love of and skill for fishing and croquet during his family’s stays at their cabin on a small island in the Les Cheneaux Islands near Hessel, Michigan. He also learned to enjoy golf. As a boy in winter, when he was not shoveling the family’s driveway for the nickel his father would give him for same, he might be found sledding on the many hills of the city. A story January 31, 1910 notes that, the prior Saturday (Jan. 29), an 11-year-old Penfield Seiberling spent several days at City Hospital following a sledding, or “coasting,” accident on North Summit Street, just blocks from his home. The hill of the street and north of it went into the current Cascade Village area and must have been superb for sledding, one did not have an accident! Quotes from the newspaper story show the dangers of losing one’s concentration:

“Young [Penfield] Seiberling and some other boys were coasting on North Summit Street. He had started down the hill first, and while going at top speed was busy watching a boy chase a chicken, with the result he lost control of hiss led and crashed into a telegraph pole. Before he could recover himself, the boy immediately following, ran into him, and with the end of the sled, cut a deep gash in Seiberling’s leg. Park’s ambulance was called, and the injured boy taken to the hospital. His condition Monday morning was improved.” – The Akron Beacon Journal, Monday, January 31, 1910.

By 1911, at age 12, his father brought Penfield into the offices of Goodyear to run general errands as an “office boy” in the company’s headquarters, which were two miles east of his home on East Market Street. By 1913, Penfield was attending high school at the Buchtel College’s high school, the Buchtel Academy. To further round out his education, he attended the Culver (Indiana) Military Academy’s Summer Naval School during the summer of 1914. From Fall 1914-Spring 1917, he spent the rest of his prep (high) school years at the Lawrenceville School in Lawrenceville, New Jersey, from which his two brothers, Fred and Willard, had graduated years earlier. While at Lawrenceville, Penfield discovered interests and talents that would serve him well all his life. He engaged his enjoyment of performance by joining the dramatics club, he honed his skills at writing while at work for the school newspaper, and his leadership skills were born when he was elected vice president of the school’s Young Men’s Christian Association. He earned his best marks in Biblical instruction and elocution – a skill he would be known for throughout adulthood. His worst grades came in Latin, French and science. During a few summers, when the family was not “up north” at Hessel, he worked for his father at Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company performing general chores.

Lawrenceville would also provide the basis for his greatest lifelong friendships with young Larry Keyes (Long Island, NY), John H. Leh (Allentown, Pennsylvania), and future author-adventurer-lecturer from Memphis, Richard Halliburton. One or more of these men, joined in college by Kansas City native Irvin O. “Mike” Hockaday, would be his roommates throughout his years at Princeton.

Penfield thrived in college. His personality, always genial and with a heavy sense of humor and fun, endeared him to classmates and professors alike. His short stature, like that of both parents, earned the nickname “Shorty” during his days at Lawrenceville and Princeton. By the time he graduated in 1921, his classmates voted for him to deliver the prestigious “Ivy Oration,” a coveted opportunity to speak to Princeton’s graduating class and their parents at the planting of the Class of 1921’s ivy, intended to climb the walls of the school’s oldest building, Nassau Hall. “Shorty” focused his coursework on economics and finance after seriously considering a major in religion. Throughout his career at Princeton, he took a variety of history, religion, literature, poetry, and astronomy courses – all of whose learning he would draw on and explore further during his adult years. He was also on the debate team; was a member of the conservative philosophical group, the Philadelphia Society; acted in Triangle Club theatrical productions (a membership he would share with later Princeton alumni Jimmy Stewart, Joshua Logan and Jose Ferrer); was the manager of the baseball team; and worked on the Freshman Herald yearbook. He attended Princeton at the tail end of future author F. Scott Fitzgerald’s days as a student. Other schoolmates during his tenure included Harvey Firestone, Jr., Foster Rhea Dulles, and a distant cousin, Thornton B. Penfield, Jr.

“Shorty’s” friend from prep school days, Richard Halliburton, was an adventurer in the purest sense of the term – he traveled overseas to Europe in 1919 on a freighter, on which he worked to make money to travel through the continent. That year, and after his years at Princeton, Halliburton traveled to the farthest reaches of the globe, where he frequently experienced third-world conditions, which he wrote about in a series of autobiographical travel-adventure books. The first of these, the “Royal Road to Romance,” opens with a passage describing what he considered his roommates’ mundane existence as students at Princeton, and he mentions all four by name, including Penfield. Halliburton circumnavigated the globe in 1930 in a small biplane, whose stories yielded another book and lecture series. He followed the footsteps of legends, swimming the Hellespont, climbing the Matterhorn, visiting the Taj Mahal, and – in his last adventure – piloting a Chinese junk, the Sea Dragon, in an attempt to cross the Pacific Ocean from Hong Kong to San Francisco for the Golden Gate International Exposition in 1939. He had told his dearest friends that, should they ever receive a telegram message from him with the words, “Wish you were here,” they should know that he was at death’s door. In fact, the second-tolast communication from the Sea Dragon during a cyclone in March 1939 included the line “Wish you were here instead of me,” and Penfield and his friends knew Halliburton had died long before he was declared dead later that year. News of his death competed with that of growing fears of war in Europe. Halliburton visited Penfield and his family in Akron several times during speaking trips – both at Stan Hywet Hall and his home on North Portage Path.

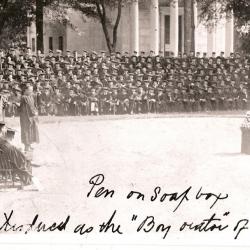

During his freshman year at Princeton, Penfield was interested in trying to get into the early flight schools attached to the U.S. Army; his patriotic fervor was such that he implored his father for permission to learn to fly, comparing himself to classmates who were leaving school to do so. Like his classmates, Penfield took courses in drilling and basic artillery and other military skills at Princeton, but he would not be eligible for the draft until the third registration in September 1918. Having already sent one son overseas, his father encouraged him to attend school for another year or until he was drafted. Figure 4: At Princeton’s June 1921 Commencement, “Shorty” Seiberling is honored during a classmate’s “history of the class” presentation as best orator by being given a soapbox on which to stand. By the time the year was up, the war had ended. Penfield’s older brother, Fred, was an officer in the U.S. Army who served in France; his cousin Charlie Seiberling, Jr. served in Italy during the war.

Penfield contemplated entering the ministry, and complemented his faith with action by volunteering at the State Home for Boys in Jamestown, New York. One hundred years ago this summer, from mid-June until early September 1920, he volunteered on a mission with British-born medical missionary Dr. Wilfred Grenfell and others in the isolated northeastern reaches of Canada. The group’s work involved the delivery of “medical, sanitary and educational” needs to the native peoples of Labrador, who were Innu and Inuit. Despite marrying an active Presbyterian, Penny Seiberling never left the church of his baptism, Holy Trinity Lutheran Church, on North Prospect Street in Akron. He supported the church cofounded by his grandfather, John F. Seiberling, all his life, and his funeral was held there.

When he graduated from Princeton in June 1921, his father had, only days earlier, resigned as President of the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company and walked away from the company with his brother, Charlie Seiberling. His father asked Penfield to help him on his next venture – to raise money for and launch a new rubber company that would be called Seiberling Rubber Company. He could not turn his father down, so Penfield’s first post-university job was soliciting funds from his father’s many acquaintances to invest in the new concern. He then went to work as a salesman for the company, based in Chicago and covering the Midwest. His challenging job was to convince service stations and tire dealers to sell Seiberling tires as slightly expensive, high-quality replacement tires. It was challenging because the “big four” tire companies were already so entrenched in so many of these stations. He had to convince them either not to sell Goodyear, Firestone, General or Goodrich tires, or to sell Seiberling Tires in addition to them. He wanted to achieve on his own merits, and so used the name “James Penfield” when he represented Seiberling Rubber. Over time and with persistence from men old and young, like Penfield, the company established a national network of dealers in small and large service stations and stores.

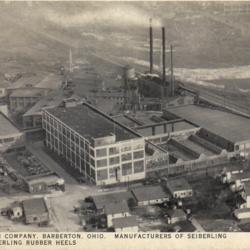

Following two years of work selling first investment shares, and then tires, for Seiberling Rubber Co., Penfield entered law school at the University of Michigan in fall 1923. He entered law school a married man, for he had married in February his lifelong sweetheart, Harriet Robinson Manton, whose father was president of the Robinson Clay Products Co. After earning his law degree in 1926, he settled into a new, Roy Firestone-designed Italian stucco home on land given as a wedding gift to him and his wife by his father-in-law, Henry Manton, and went to work for the Slabaugh, Seiberling, Huber & Guinther law firm in Akron. (The “Seiberling” at the law firm was his father’s first cousin, future U.S. Rep. Francis Seiberling. Penfield’s cousin, Robert Seiberling Pflueger, would also become an attorney and partner in this firm.) By late 1927, he had joined the Lambert Tire & Rubber Company in Barberton to manage sales. The company did not survive the Great Depression and was liquidated. In 1931, with a variety of sales, operational and legal experience under his belt, he rejoined his father and uncle at Seiberling Rubber Company, where he was appointed sales manager in 1932 and became president of the company in 1938. By the 1940s, the company was the seventh largest seller of tires in the nation, and Penfield was at its helm, becoming chairman of the board in 1950.

Penfield’s years running the Seiberling Rubber Company were years of upheaval and growth in the United States. World War II put the Barberton and Canadian factories on a war footing, when it won government contracts to build halftrack and truck tires, pontoon boats, pontoon bridge floats, fuel bladders to line fighter planes, heels and soles for GIs’ boots, life preservers, and gas masks. Penfield had to travel to Washington, D.C. and lobby for the contracts, an experience that forever tarnished and jaded his view of politicians and the workings of the federal government. Seiberling Rubber continued to sell replacement tires and advertised products to help repair tires to help them last longer during wartime rationing. In Penfield’s correspondence with his younger brother, Franklin, and five nephews who served in the U.S. Army and Army Air Corps, he would describe the progress of the factory’s output as well as the general challenges the company faced. Following the war, the company grew along with the nation’s postwar boom, introducing “safety tires” and “selfcooling” tires to customers who were purchasing automobiles at accelerated rates. To show the wear of a major competitor’s tires, Penfield would often drive his car on Firestone Tires and point out tread wear to customers and employees alike!

By late 1954, Penfield would begin to face his longest and greatest struggle at Seiberling Rubber: the gradual purchase of stock, and directorship power, by industrialist Edward Lamb of Toledo. A selfavowed socialist who owned multiple commercial ventures, including radio and television stations, Lamb saw an attractive takeover target in the productive – but, he thought, inefficiently run – Seiberling Rubber Company. He had purchased family-owned businesses en route to amassing his own corporate empire, and he saw the company as another potential acquisition. Lamb became a vocal critic of the company’s leadership and selected decisions and initiated a proxy fight in late 1955 to take over the company. In response, Penfield marshaled a concerted public relations campaign, contacting every single Seiberling stockholder, but one, who was out of the country, to address Lamb’s criticisms and explain the health of the company and the efficacies of decisions he and the board had made regarding investments, sales, products and operations. The Seiberling board beat back challenges by Lamb at the annual stockholders’ meeting in 1956. However, by 1961, Lamb had purchased enough shares to have five of his representatives, including himself, on the board. To attempt to appease the Lamb directors, Penfield stepped down as president, remained chairman, and the board elected Harry Schrank president. By February 1962, Lamb had purchased enough shares to win a majority of board seats, and Penfield resigned, leaving the company out of family hands for the first time since its founding. Despite promising to invest in the rubber manufacturing plant and to maintain and grow the company’s operations, within three years wracked by declining sales, Lamb had sold off the rubber manufacturing portions of the company, including the rubber plants in Barberton and Canada, to Firestone Tire & Rubber. Seiberling’s tire producing arm thus became a division of its onetime competitor, Firestone, and Seiberling-branded tires of the now Bridgestone Corp. are still available.

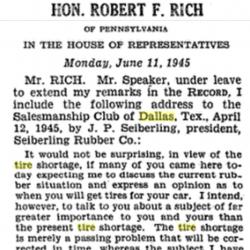

The loss of the company his father founded was a heavy blow to Penfield; the stress he endured during the proxy fight and years of challenge by Lamb took a toll on him. It especially bothered him to lose the company to a man who professed economic and political values so in opposition to his and his father’s, which were those in firm support of personal liberty and capitalism as an engine of growth and human progress. In fact, one of Penfield’s greatest speeches, titled “Freedom’s Greatest Foe,” was entered into the Congressional Record in June 1945. In the speech, which he gave to the Salesmanship Club of Dallas, on April 12, 1945, Penfield decried the growth and acceptance of collectivism in the world, and advocated for a rebirth of support for and understanding of the benefits of individual liberty and how to preserve it.

In contrast to the stresses of his later business life, Penfield’s home life was always a very happy one. He appreciated the blessings of the family he was born into, and the one that he made with his wife, Harriet. Their first child, a boy named for his father, was born in October 1924 and died after only three days – an early tragedy that made them fear they might never have another child. Their second child came four years later, in October 1928, and was named Mary Margaret for her maternal grandmother and aunt. Another son, James Henry “Jim” Seiberling, came along in 1936. Between them, they would give Penfield six grandchildren. His first grandchild, a girl, was born on his 60th birthday and given his middle name as her middle name. He received the joyful news from his son-in-law during his previously planned party at home. He also cared deeply about his nieces and nephews and regularly wrote to them, giving and asking for family updates. Upon discovering that a nephew -- who had been held prisoner of war for 13 months at Stalag Luft XVII-B during World War II – was recovering from post-war illness in a hospital at Fort Dix, New Jersey, Penfield hopped on a train and visited young Edward “Ned” Handy in the summer of 1945. Ned recounted the value of this visit to his spirits many decades later; he was so grateful to see a caring family member during a tough recovery.

Penfield and Harriet were married for 50 years. They traveled the country with their children when they were young, joining business trips to Seiberling dealers with the great historic and geological sites of the country. For recreation, he and Harriet would meet once a year in the Poconos with their friends from college and play lengthy poker and bridge games while enjoying the mountain scenery. He was, at first, despondent following her death in July 1973. His optimism and faith carried the day, however, and he chose to remain active with his children, grandchildren, and local friends, corresponding with friends who lived out of town, going on fishing trips, following politics, playing croquet with friends, and working on the board of trustees for Stan Hywet Hall & Gardens. He held family gatherings in his home and took many photos that the family cherishes for their memories. Some of his greatest gifts to those who knew him were mentoring and inspirational letters filled with wisdom and lessons of overcoming obstacles, which he wrote to his grandchildren, nieces, nephews and cousins younger than he. He was a verbose writer, but as such, he shared much contemporaneous history and explained his reasoning and thinking in detail, and he drew references from a lifetime of reading classics, literature, poetry, and political and economic thinkers of the day, and a business life in which he encountered standard -- and many unusual -- problems regarding operations, personnel, sales and leadership.

Penfield Seiberling was raised to be a civic-minded and engaged citizen. His list of philanthropic activities is long, and it is notable for the time he invested in all the institutions on which he served as a board member or engaged member and supporter. Letters and archives of his notes attest to the fact that he refused to be a “figurehead” board member or one who did not perform due diligence and oversight of the organizations he served. He was invested in the good governance of the institutions he served. For many years, he served the boards, or as a member, of institutions such as: the Akron Bluecoats (police benevolence organization); the Akron Astronomy Club; the Akron Community Trust (now the Akron Community Foundation); People’s Hospital and Akron General Medical Center (now Cleveland Clinic Akron General); the Navy League; Old Trail School, whose existence he helped preserve during some lean years; Princeton University; Sons of the American Revolution; Sumner Home for the Aged (now Concordia at Sumner); and as the spokesperson for the family donors, and second family representative to the board, of Stan Hywet Hall & Gardens. He also privately helped and mentored many people, including German relatives left destitute in Bad-Wurttemberg following World War II. Beyond Seiberling Rubber Company, his professional involvements included: serving as a charter member of the Advertising Club of Akron, which named its annual awards the Penny Awards (now the Akron ADDY® Awards); the Akron Chamber of Commerce; and the Rubber Manufacturers Association. In addition to Akron’s business leaders and his famous college roommate, Penfield met other famous individuals, including:

— Helen Keller, who put her fingers on his lips and jaw in order to converse with him (he was 26 and home from law school during her visit to Stan Hywet Hall in December 1924)

— Then-Lt. Col. James Doolittle, during his visit to Akron at a Chamber of Commerce event, January 1942 — The von Trapp family and their priest, Father Wasner, when they visited and sang at Stan Hywet in January 1942

— Rep. and future U.S. president Lyndon Johnson, whom he had to work through to win war contracts for Seiberling Rubber Company.

He also corresponded with economic thinkers such as Ayn Rand and Leonard Read, and he supported the fledgling Foundation for Economic Education.

The death of his father in 1955 – and the problem of “what to do with Stan Hywet” – coincided with the initial corporate attacks by Edward Lamb. Thus, during the years of challenge to Seiberling Rubber Co., Penfield was also dealing with his five siblings about the future of their family home – a home too large and expensive for any of them to own, operate or maintain. (Interestingly, second only to his sister Virginia, Penfield spent the least amount of time living in Stan Hywet of any of the siblings. When the home was completed in December 1915, he was spending most of his year away at school, and he moved to Chicago by early 1922.)

By the time F.A. Seiberling had died, on August 11, 1955, all of his children were middle-aged and had families of their own. His oldest children were living at Stan Hywet; Fred was separated and Irene widowed. Discussions by letter and in person about Stan Hywet had occurred for years without resolution. After attempting to donate the home and contents to the University of Akron, the city, and the state – none of which wanted it – the siblings held a meeting of interested community members in the spring of 1956 in the Music Room. Although at first very skeptical of the idea of turning the home into a museum, Penfield eventually agreed with his siblings to give the home to the newly founded Stan Hywet Hall Foundation over a seven-year period, from 1957 to 1964. Letters indicate that those early years were challenging for all involved in the running of Stan Hywet, but they also show his change of mind, confidence level and commitment to supporting the institution and its mission. He was impressed enough with -- and grateful for the success of -- those early volunteers, operating board members and donors that he remarked, years later, that Stan Hywet’s survival was a product of the love and dedication of those who undertook to make it a museum. He said in 1980: “brick and mortar and greensward can reflect SPIRIT, and there is no place where that is more evident than right here at Stan Hywet Hall.” He emphasized to his grandchildren that Stan Hywet was saved by enthusiastic and creative volunteers and donors. Penfield would serve as the Seiberling family representative on Stan Hywet’s operating board until his death, from lung cancer, in 1982.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Thanks to his birth year, Penfield Seiberling would have been among the last to fully witness the transition of transportation modes from the once-dominant horse-drawn carriage and carts, streetcars, and railroads to those of automobiles and planes. He would live through the rise of the balloon, airship and blimp (even taking a five-hour ride in a an early Goodyear balloon in 1915), the trials of the Wright brothers regarding air flight, the rapid increase in deadly firepower of weapons of war, two world wars and two more regional conflicts, and the use of jet propulsion and the entry into the atomic age. He knew an era without radio and television and died just as the personal computer was becoming ubiquitous. He would have listened to music either live or on a Victrola, and later a radio; his children would dance to music from vinyl records; and compact discs were coming into vogue when he died in 1982. The telephone was in its infancy when he was born, and he would just miss the cordless phone in wide use. The country was electrified and automated in many ways during his lifetime, and exploration reached the moon when he was 71 – an event he had hoped to see as expressed in a letter from the early 1960s. He also witnessed booms and busts, living through three economic depressions in his life (1920-21, 1929-1945, the mid-1970s-1982). His faith, family and ability to persevere supported a general sense of optimism that pervades his letters to friends and relatives. He trusted the human spirit and was confident that the United States was the best nation on earth, because he believed its liberty gave anyone who lived here a real chance to succeed.

Written by Summit County Historical Society member Harriet Chapman on July 3, 2020.

IMAGE SOURCES:

1. James Penfield Seiberling, circa 1901. Source: Stan Hywet Hall & Gardens.

2. James Penfield Seiberling at bat, circa 1905. Source: Stan Hywet Hall & Gardens.

3. “Shorty” Seiberling at Princeton. Source: Nassau Herald, Class of 1921, Princeton University.

4. At Princeton’s June 1921 Commencement, “Shorty” Seiberling is honored during a classmate’s “history of the class” presentation as best orator by being given a soapbox on which to stand. Source: Chapman Family.

5. F.A. Seiberling and J. Penfield Seiberling in Honolulu, Hawaii in early December 1931, during their national tour to meet with 5,000 Seiberling Rubber Co. tire dealers. They met Seiberling’s major tire distributor and Hawaiian Seiberling dealers, to whom F.A. Seiberling introduced the company’s newest tire, the “air-cooled super triple-tread.” F.A. also gave a speech to local dealers and to the Rotary Club of Honolulu during their sojourn. Source: Chapman Family.

6. Image of the Seiberling Rubber Company on 15th Street NW in Barberton, Ohio, from the late 1920s (left). Source: Chapman Family.

7. Image of the Seiberling Rubber Company on 15th Street NW in Barberton, Ohio, from the 1940s (right). Source: Chapman Family.

8. Screen capture of the title and opening remarks of Penfield Seiberling’s speech to the Dallas Salesmanship Club in April 1945. Source: The Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 79th Congress, First Session, Appendix, Volume 91, Part 12, June 11, 1945- October 11, 1945, p. A2800. United States Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

9. J. P. Seiberling, Harriet M. Seiberling and their children, Mary Margaret and James Henry “Jim,” circa 1939. Source: Stan Hywet Hall & Gardens.

10. Penfield Seiberling with his parents and siblings inside Stan Hywet Hall, circa late 1917. He and his siblings were the future donors of Stan Hywet; Fred’s three children would serve as donors of his share. Seated, L-R: Virginia, F.A., Franklin, Gertrude, Willard, Irene. Standing, L-R: J. Penfield, Henrietta (Fred’s wife). Source: Chapman Family.